In 1957 I was fifteen. Eisenhower, a member of the Lost Generation, was President. He had recently agreed to defend Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan against invasion. Nixon, a member of the Greatest Generation, was his Vice President. The Civil Rights movement was just beginning. Newspaper headlines revealed there was a Mad Bomber on the loose and the Ku Klux Klan was making big trouble, We were in the midst of the Cold War with daily reminders of the nuclear bomb threat. We practiced drop drills. People were building bomb shelters. Elvis was on every radio, which was, no doubt, why the Everly Brothers couldn't get little Susie to wake up and Buddy Holly was distraught because Peggy Sue had to get married. There were four stage-one smog alerts that year, which meant it was dangerous to breathe.

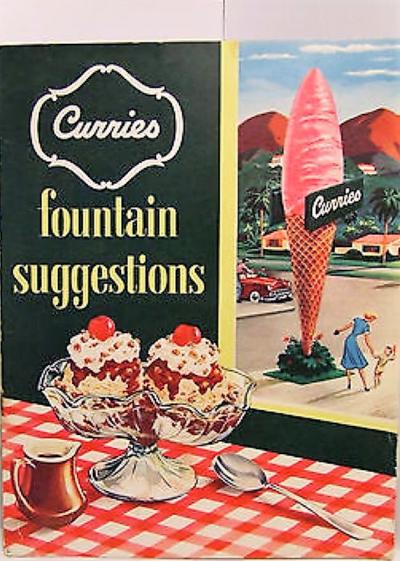

My generation is called the Silent Generation. I thought I belonged to the Worried Generation. And with plenty of good reasons. But my mother just considered me neurotic and thought the best cure was to keep me busy. She had already brokered babysitting jobs for me all over the neighborhood from the time I was eleven. But at fifteen I guess she thought it was time for a real job. So instead of diapering babies and chasing toddlers of the Boomer generation for fifty cents an hour, I was brokered into a job at the local Curries Mile High Ice Cream parlor for seventy-five cents an hour. Her part of the deal was that I would be out of the house and she wouldn't have to be annoyed by my worrying.

After my first day of training, I did have a lot on my mind. I mean that was a highly responsible job with many possibilities to do real harm! What if I broke a glass and it got into the ice cream and someone ate it and died? What if I poisoned someone by not cooking the frozen hamburger to the right temperature? I knew what food poisoning was! I could wind up in jail!

My mother: "Oh for Pete's sake, just go to work!"

So I went. Worried.

Making an ice cream cone that was a Mile High was a big responsibility. It was the company's trademark, and you had to get it right. You had to take that pointed trowel shaped tool and jam it hard into the solidly frozen ice cream, turn it to make a perfect cone, pointed at the top and wide at the bottom, and if you did it correctly that was a about an eight-inch tower. Then you had to take the wide part and put it in a sugar cone. Only problem was, the wide part of the ice cream was bigger than the opening at the top of the cone. I developed a technique, eventually, of balancing it carefully and then taking the point of the trowel and carefully pushing the edges down into the cone as far as I could. That way it would stay intact until the customer got out the door. If it fell apart before they passed that threshold I would not only have to make another, but clean up the mess.

After a few days I began to feel more confident. I hadn't killed anyone, as far as I knew, and I hadn't broken any glass. And I was meeting some interesting people.

There was an older woman who came in on weekends or evenings to help out. During the day she was a seamstress. She talked about the gorgeous formal gowns and nightgowns she crafted. I longed to see them. She finally revealed that she only made the front of any garment, because she worked for a funeral parlor. It's easier to dress a corpse if there's no back.

I'm pretty sure the couple who ran this ice cream parlor were members of the Greatest Generation, although looking back I have my suspicions that she might have been from the Lost Generation. They liked to take a walk after dinner, and would leave me to manage on my own while they went down to a little place called the Swiss Echo.

And you know, when they eventually wandered back, I could tell they were, themselves, a mile high. They took that company slogan seriously.

I brokered my own next job. It was more money, and it wasn't nearly as complicated.