THE ABILITY TO DECEIVE is a fundamental aspect of life.

-

Newly molted shrimp use aggressive displays to make potential attackers think they are stronger than they are.

-

Certain orchids mimic the signals of female insects in order to entice male insects into helping with their pollination.

-

When threatened by a predator, the caterpillar of one moth will inflate part of it's body to look like the head of a snake.

The list goes on and on.

We humans, with our highly developed brains and our social way of life, have become experts at deception in ways that leave shrimp and orchids and caterpillars in the dust.

-

We are capable, not only of lying in the moment, but of sustained and carefully orchestrated deceptions, such as the ongoing barrage of propaganda emails I've documented on this site.

-

But we are also capable of something even more dangerous—we are capable of deceiving ourselves—of ignoring clear evidence that we are mistaken, of refusing to think about alternative points of view, of confusing questions of fact with questions of morality—telling ourselves that it would be wrong to believe a certain fact, even if it were true.

These two skills—the ability to lie in a sophisticated and consistent way to others and to ourselves—are both a great protection (think of the famous Nazis at the door) and a great danger: to humanity as a whole, to our country, and to each of us as individuals.

To compensate for this danger, we have evolved a built-in value: we value the truth.

In the dailiness of our lives, we are constantly trying to discern the truth: which is really cheapest laundry detergent, does she really like him, what's the real reason that neighbor sold their house, where did I really leave those keys?

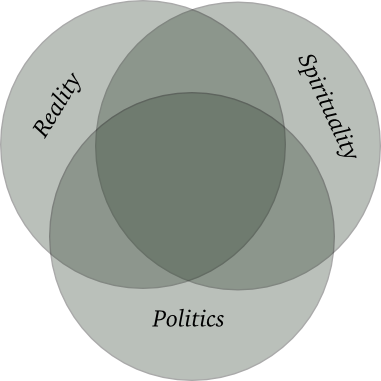

But reality contact is only one of our values, and when knowing the truth conflicts with values like being part of a group, or not wanting to admit we were wrong, or protecting our families, we often find ourselves embracing lies.

Why do we do this?

Most often because we are scared.

Think about the last time you told a lie, or resisted facing the truth.

The chances are very good that you didn't do it out of pure nastiness or evil.

You very likely did it because you were either afraid of what would happen if you didn't, or afraid that something wouldn't happen if you didn't.

We embrace unreality because we are afraid of reality, and this works in two ways:

-

We fear that the truth will itself be too painful, or

-

We fear the consequences of acknowledging the truth.

So making contact with reality becomes a matter of courage, but also a matter of trust.

The two go hand in hand:

-

On the personal level, we are afraid to examine our own motives because we don't trust our own essential goodness.

-

On the interpersonal level, we are afraid to trust others because we don't trust the essential goodness of our friends and acquaintances.

-

On the political level, we are afraid to do what we know in our hearts is right because we don't trust the essential goodness of all those people we don't know personally.

And we are not always completely wrong.

As you read the list above, there's a good chance that you were intrigued by the personal level, a little suspicious about the interpersonal level, and even a little cynical about the political level.

The further we get from ourselves, the more we need the skill of discernment—the ability to judge when to have the courage to trust, and when to have the wisdom to be wary.

But developing that wisdom, and that discernment, begins at the personal level—begins with the courage to trust ourselves.

Next time: more on courage, trust, and reality...