Let's begin small, with my coffee mug. I have a coffee mug sitting on my desk. But it lives in a different world than I experience.

We all live in two worlds, but only experience one.

- The outside world—the one that contains ourselves, and other people, and rocks and trees and galaxies and snails—is a world that we have no direct experience of.

- But there is another world inside our heads which contains the images of people, rocks, trees, etc. that we are familiar with. This is the world we live in—not the outside world.

All that we know about the outside world is contained in our inside world, but this knowledge is always both limited and distorted.

To begin with, Everything we know about the outside world comes to us through a handful of senses: sight, hearing, feeling, smell, taste, and a couple of other, less obvious ones. Each of these senses has a limited range. We can only hear certain pitches. We can only see certain wavelengths of light. We can only detect motion if it is fast enough.

But those senses don't just limit our access to the outside world, they structure it as well.

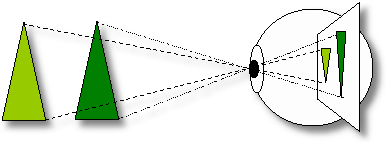

For example. In our inside world (the world in our head) things look smaller when they are farther away. This is so much a part of the world we live in, that we seldom question it. But, in fact, it is not a truth about the outside world—it's a truth about how our eyes work.

Because the image is flipped inside the eyeball, and the distance to the retina remains the same for all images, a more distant object makes a smaller image on the retina. If our eyes were made differently, this wouldn't happen.

The outside world knows nothing of perspective, as far as we know, but the world we live in—the world in our heads—is never without it.

That's what the old question about the sound of a tree falling in the forest is really about.

Trees don't make sounds, as far as we can tell. Trees, when they fall, create vibrations, which, if we are present, cause our eardrums to vibrate, triggering nerves, which eventually get interpreted in our brain and experienced as sound.

The same could be said for color—what exactly is the connection between the experience of "blue" and a particular frequency of light-wave? Most probably nothing more than the way our minds interpret the input that frequency triggers in our eyes.

It's really amazing, when you come to think of it, that we manage to know anything at all about the world out there.

Back to my coffee mug. I am as familiar with it as I am with anything. Yet the mug I know partakes of color and perspective, makes a sound when I put it down, feels warm (not jiggly).

The mug I know, and the mug-as-it-is are two quite different objects. The mug I know exists inside my head, and, in a real sense, I know everything there is to know about it.

But the mug-as-it-is exists in the real world, and—although there are important and helpful connections between the two—the mug-as-it-is remains a mystery to me.

A minor mystery to be sure, but we're only beginning our journey.

Stay tuned for part 5.