In the end, I guess I'm grateful to Richard Dawkins for the Out Campaign, primarily because it has made me think about the whole issue of atheism, god, and religion much more carefully—and I wouldn't have thought that was possible.

Today, in particular, as I contemplate putting his Scarlett A on my site, I find myself thinking about what atheism actually means, and what it doesn't mean. It's much more complicated than I had realized.

Take the simplest, bare-bones, definition:

An atheist is a person who does not believe in God.

It seems simple enough, but then one has to ask what the word "God" actually means.

The standard concept of God in our culture was forged over the last two thousand years or so, primarily in the fires of ancient Greek philosophy, medieval culture, and the theology of the Roman Catholic Church. Few protestants, and fewer very conservative protestants realize just how much of what they believe was invented by Roman Catholics, long after Jesus, Paul, and the Early Church Fathers were dead.

The result is an authoritarian creature, based on the model of a king, quasi-human, quasi-superman, invisible, in charge of the whole universe but intimately concerned with the tiniest detail of everyone's daily life, who requires not only absolute obedience but also obeisance, is absolutely good, but thinks that eternal punishment is appropriate for temporal misdemeanors—the chief of which is, in most cases, not believing in his existence when he refuses to give us any solid evidence: in fact, punishment for behaving rationally.

No. I don't believe in that God. In fact, I would argue that that God is a contradiction in terms—that the concept disproves itself.

Many Christians will read that last sentence as a rejection of God—that is, as a rejection of a person. It is not. It's the rejection of an idea. I am not standing before the creator of the universe, and screaming "I don't believe in you." I am standing before a bunch of theologians, and saying "I think you got it wrong."

To paraphrase the advocates of Intelligent Design: God is just a theory. It's a theory that I think is mistaken. The reason I think it's mistaken is that (unlike, say, radio theory or the theory of evolution, or quantum electro-dynamics) there is no real evidence for it.

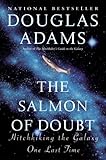

I do, however, with Douglas Adams, tend to believe that there are artificial gods. To put it another way, there are many religious people who see the god-idea, not as a description of the physical world, but as a cultural and personal tool, an abstraction about their community which enables them to practice their faith. You will be unlikely to find such people bombing either trade centers or abortion clinics. And you will be unlikely to find them trying to force their beliefs on others.

Many atheists would claim that all religion is bad. I doubt this, in both senses. That is, I doubt that there are no good religions—I've named a few I like on this blog—and I doubt that there is any religion that has no good in it. This seems absurd. Why would it last?

We are at a point in history when part of the world is coming to understand that certain traditional ideas—like the traditional theory of god—were mistaken. We are also coming to understand that certain institutions—like traditional religion—are flawed. But it would be a grave mistake to throw the baby out with the bathwater. We are nowhere near understanding the big picture—how humans form communities, how those communities can go wrong, how to even know what it means for a community to go wrong for sure. There's room for a little humility.

Many atheist are also materialists. They claim that the material world is all that exists. I can only go so far down that road.

First, some distinctions. One can reject the god-theory without rejecting the supernatural. I happen to reject both, but they are not the same. It is possible to not believe in a god, and still believe in ghosts, fairies, or Santa. there's no necessary connection.

Likewise, one can reject god-theory and the supernatural without rejecting the spiritual. This is where I part company with many other atheists. And I do it on the same basis that I part company with traditional religion—evidence.

The traditional Christian view is that our conscious experience is evidence of a soul—a "me" that lives inside my body, peers through my eyes, tastes with my tongue, but in the end is separate from my physical body, can go to heaven when I die while that body stays here on earth, can have experiences which don't involve the body, such as direct experience of God, and can be put into a new body when Jesus returns.

Most atheists reject this idea—obviously the parts about heaven, God, and the return of Jesus, but more fundamentally the idea that there is a soul, separate from the physical body. They're probably right about this. All the evidence of brain research seems to point to thought, emotion, and sensation as intimately connected to the structures and functions of the body: particularly of the brain. This seems on the face of it to call the idea of an independent soul into question. When an electrode stimulation in this part of the brain can predictable cause a person to feel a certain emotion or think a certain thought, there seems to be little need for some supernatural entity to do the feeling and thinking.

But many atheists go beyond this point, and either deny the existence of conscious experience altogether, claim it is merely an illusion, or simply ignore the issue as trivial and not worthy of examination. I think they are mistaken.

The reason I think they are mistaken is the evidence of conscious experience itself. It is my only connection to the "outside" world. I would know nothing of science, of physical reality, of atheists, if it weren't for my conscious experience. Yet, the physical descriptions of brain activity—however well they correlate—don't come remotely close to describing those experiences, let alone explaining them.

My own current theory—held lightly, and open to change—is that the universe-as-described-by-science-so-far has another, internal side, which is the universe-as-experienced-from-within. There is a profound difference between everything you could learn about me—or I, about you—from exterior, physical, examination, and the experience of being me. And it is a difference of kind. I don't think there's an immaterial soul haunting my body, but I do think there's a spiritual side to the material world. Pain is a reality, even though you will never find one when dissecting a brain. I'm only staking the position out, at the moment, not defending it, because I am well aware just how strong the full-going materialists' defenses are on this point.

But I will say where I think my atheist friends are making their mistake.

This inner life, the realm of consciousness as experienced, the spiritual realm if you will, is part of the territory that had been staked out by Christianity, and by religion in general. In the current political climate, there is a political war on—a struggle for control of the culture that was initiated by extremist religion. Atheists have, quite rightly, joined the political fray—fighting to stop religion from dictating that lies be taught in science classes, or that teachers be allowed to force children to pray in schools.

But it is a mistake to allow a political battle to define ones position on an issue of science or philosophy. I strongly suspect that my extreme materialist friends find it difficult to acknowledge the spiritual side of the world because it feels like a capitulation to religion, or to a religious world-view. It was a materialist approach, focused on externals, that helped them to forge an alternative functional worldview, so naturally they would like that approach to cover everything.

I think they are mistaken. I think that they are denying the one part of reality we can be most certain exists, and, moreover, I think that an unwillingness to examine it will always make them sound a little foolish to the common person.

So, if pressed, I would call myself a spiritual atheist. I don't think the god-theory stands up. I don't believe in a separate, supernatural or non-physical realm. But on the other hand, I'm quite sure there is more to the world than can be viewed through a microscope. The physical world has an inside as well as an outside, and it's worthwhile trying to map it, and correlate it with what we know of the exterior.

When I put the A up on my site, that is what it will mean.