THREE POSTS AGO (in this series) I asked four questions:

- Who invented this way of thinking—this idea that the human race (including you and me) is fundamentally flawed, that we are, at our core, bad in some way?

- Is there any reason to believe it's true?

- If it's not true, what is the truth about humans?

- How do we get from here to there?

The parable in the previous two posts is an answer of sorts to the first question.

It's not intended to be taken in literal detail, but rather as a kind of general indication of what may have happened, historically.

What we know is that:

- prehistoric humans developed a highly egalitarian, hunter-gatherer, culture in which liberty, equality, fairness, and mutual care were fundamental values, that

- roughly 12,000 years ago, shortly after domesticating dogs (which have a naturally hierarchical social structure) humans began to form hierarchical structures themselves, that

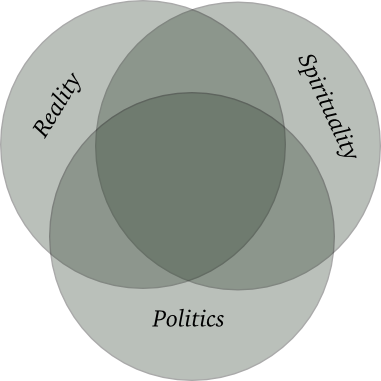

- these hierarchical structures were both political and religious, involving belief in super-powerful gods, the idea that humans needed hierarchically enforced laws, and the idea that the rich and powerful who enforced these laws were agents of those gods, and that

- these new structures quickly undermined liberty, equality, fairness, and mutual care for all but the most wealthy and powerful.

The exact cause and effect chain is something we will probably never know in detail—and not really something we need to know.

Even if the parable is wrong in the details, it's useful as a metaphor for the position we find ourselves in.

We have, in whatever way, come to view humanity as fundamentally flawed and therefore in need of constant correction by some exterior authority—whether that authority be religious, or moral, or legal, or military, or corporate.

Hand in hand with this idea comes a second idea: that some kind of hierarchy is necessary in order to keep us humans in line.

And, consequently, our idea of morality has come to be something more like dog-training than the implementation of truly human values.

Are these ideas—that humans are in some sense bad, and that we therefore need to be trained out of our badness by some authoritarian structure, in fact, true?

The answer to that question, depends, in large part, on what we mean by terms like good or bad.

In the dog-training paradigm, the answer to that question is very simple.

A good dog is one that pleases its master—a bad dog is one that displeases its master.

It's easy to see how this concept of goodness and badness leads directly to a hierarchical view: morality itself is a matter of hierarchy under this model.

If there is no master, there can be no good or evil.

And, in fact, that makes perfect sense.

A dog without a master—a dog that has never been domesticated—is, in fact, a wolf.

And it makes very little sense to talk about wolves, as a species, as either good or bad; they are just wolves.

If we follow a parallel line of thought with humans, we could consider human beings as either:

- fundamentally demonic: selfish, violent, uncaring, disrespectful, malicious, stupid, dishonest, disobedient, etc.,

- fundamentally angelic: selfless, peaceful, caring, respectful, loving, intelligent, honest, obedient, etc., or...

- simply human: a species in which individuals can be any of the above if the occasion calls for it, but which, as a species, is neither good nor bad, but simply human.

Notice two things:

- The third choice is not merely a midpoint between the other two.

Being "simply human" doesn't mean being halfway between good and evil, or half-bad and half-good. It involves a different paradigm, a different model, in which the idea of good as "what the master wants" and evil as "what the master dislikes" just doesn't apply. - If we accept the third choice, we must reconsider the master/slave (or master/dog) paradigm.

We must seek a different model of morality.

Next: Models of morality...